The Book

After a while of pushing the book from left to right I now have at last come to read Il Principe of Niccolò Machiavelli. My first impression was: Wow that is more civilised than I expected; but more on that later.

Following are some main takeaways:

Machiavelli puts great emphasis on the fact that one must have control over two classes in society: the elite and the general populace. For each of them he has his own method of accomplishing such. With the elite there is the risky method of upholding old friends (those which helped a new leader get to power) and the much more fortunate way of placing your ex-enemies into certain positions of power, thereby making them either thankful and new partners; or making them seem unthankful in front of everyone; a kind of state-disease conspiracy prophylaxis. As for the general populace, a new leader would be supposed to appear good but must also appear strong; both of which to certain extends can be but acting.

Apart from that, Machiavelli demonstrates that luck with just the right dispositions are prerequisites for all rises to power as well as most downfalls. And not to have your own military is a great jeopardy.

About the Author

The term Machiavellianism is in my opinion definitely one of those slogans which has almost next to nothing to do with what is reality.

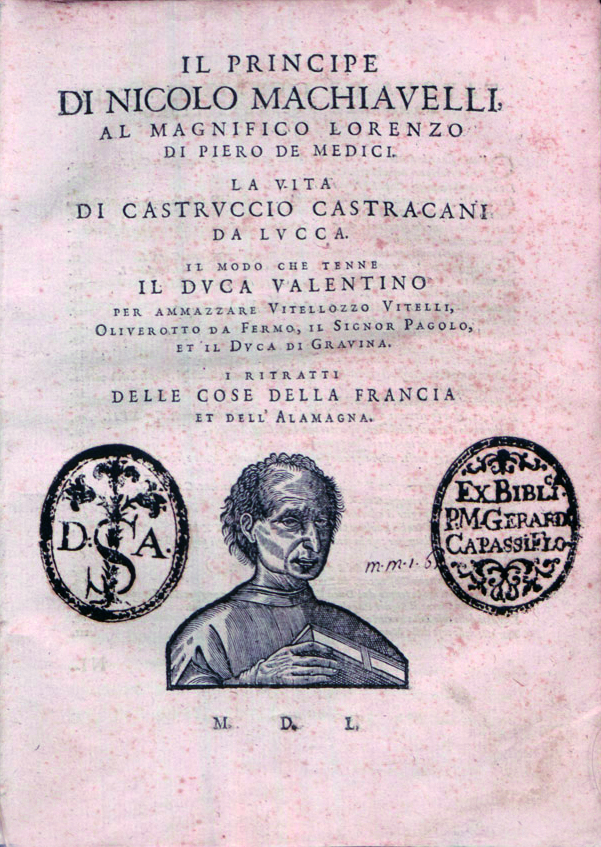

Is it not that Machiavelli (I have attached a picture of him below) was a realist of the finest degree? Has he not accurately assesed the situations about which he writes?

How then has his name become associated (and pretty much synonymous) with the view that politics is amoral and that any means however unscrupulous can justifiably be used in achieving political power (to quote from merriam-webster dictionary)?

Well, to be fair, he definitely writes about how a new ruler must not necessarily be the best in character or virtue – in fact, he teaches that this would be hindersome since you could never please all to the fullest extend and, according to him, even those which a ruler thereby would wish to please would not recognise the effort he is putting into pleasing them. But you also have to consider whether he has said something absurd; which he in most cases has not. In addition to that, by refering to what life as a ruler is like (fearing for certain things in times of crisis and putting all effort into preparing for crises in stable times), he knows fully well that it takes a special kind of character to be a ruler. And so that is just how things are in politics. Thereby it seems a little off when portraying him as some kind of Will-To-Power psychopathic state-strategist (I know that this may be a bit exaggerated); because he, afterall, just wrote what was (and is) the method by which you claim and keep power.

And now we may reexamine whether Machiavelli truly deserves the associations his name comes with. I for my part (as far as a first read can give one an impression) must conclude that Machiavelli, although being a realist, was also not more than that: Just a brute-facts realist.